Archive

Destiny of My Son’s Serbian

I am trying to speak Serbian to my son as much as I can. Whenever I can. But because I am not always consistent, I tried to come up with some guidelines. Not rules, because rules do many bad things to me: they turn me off; they make me forget (ignore) them; they make me turn my back (give up) on the whole thing. That’s why I decided to have only guidelines:

* When Andrei and I are alone, at home and in public, we speak Serbian.

* When we are in the company of others, we speak to others in English, but I always speak to Andrei in Serbian. (Now this gets complicated fast: What about the times I need to address both Andrei and another kid who doesn’t speak Serbian? What about the other “triangular” situations where Andrei and I are having a conversation with a non-Serbian-language-speaking person?)

* When my husband, Andrei, and I are spending time together we mostly speak English so we can have conversations about non-language-related things. However, we have a lot of language-related conversations as well infused with quite a bit of Serbian (How do you say “Let’s go downtown” ). And it’s lovely when Andrei or Michael switches to Serbian.

* We try to read as many books in Serbian as we can (at least two at bedtime).

* And we try to listen to a lot of Serbian music.

* And Mama sings mostly in Serbian. Read more…

Gaddafi, Libya, and Me, Part 1

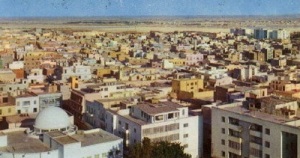

Libya’s ex-leader Muammar Gaddafi has been killed today. “Libya’s ex-leader Col Muammar Gaddafi has been killed after an assault on his home town of Sirte, the transitional authority’s acting prime minister says. … He [Gaddafi] was toppled in August after 42 years in power.”

My parents and I arrived to Libya on October 17, 1985. It was incredibly cold and snowy when we were leaving Serbia despite the fact that it was only mid-October. I said good-bye to my classmates and my teachers. Some of my teachers thought my parents were doing an awful thing – dislocating such a great student in the middle of the school year and almost at the end of my elementary schooling (I was in seventh grade).

My parents and I arrived to Libya on October 17, 1985. It was incredibly cold and snowy when we were leaving Serbia despite the fact that it was only mid-October. I said good-bye to my classmates and my teachers. Some of my teachers thought my parents were doing an awful thing – dislocating such a great student in the middle of the school year and almost at the end of my elementary schooling (I was in seventh grade).

My parents were not concerned at all about my ability to adjust to a new school, new immediate environment, new country. They simply expected I would. They would help me with schoolwork if needed, and I’d just handle the rest the way I handled another new school at the beginning of the fourth grade (they wanted me to study German instead of Russian so they moved me to a different school – that was it; I doubt they spent a second wondering what I thought about Russian and German).

My parents applied to some cultural-technical exchange program a few years before we went to Libya. It was after they lost hope that they were ever going to find work in their field in Austria, Switzerland, or Germany. It was well known that Libya needed physicians and nurses and they wanted to go. I was, of course, going to go with them. I was going to go to a new (Serbian) school, make new friends, and live in a different country. That was it.

When we arrived to Benghazi, it was still warm despite the fact that it was late at night. My mother’s colleague took us from the airport to his apartment. All I saw from the new country was the people in Muslim attire at the airport, the stretch of a highway and the city lights. That night we stayed in the house of our new friends. They had a daughter about my age, Kaca. I slept in her room that night. Interestingly enough, we didn’t talk about Libya, but about Yugoslavia. Libya was there, around us (although still totally unknown to me), but Yugoslavia was what we both left behind.

The following morning, in bright daylight, I finally saw that new country where we were going to live for at least a year and our new apartment. The landscape looked very different. We were surrounded by red sand on all sides. The land was perfectly flat, from our kitchen window you could see for miles ahead. The apartment was furnished and pretty spacious, my room overlooked the center of the village where we were going to live and the hospital where my parents were going to work. This village was called Hawari, it was a suburb of Benghazi, built around the 7th April Hospital as housing for foreign employees, mostly employees from the republics of the old Yugoslavia and the Philippines. On one side, the village was surrounded by Libyan villas (months later I was going to spend hours on our kitchen balcony studying the front yards of these villas, waiting to see a human being step out of the house; I rarely saw any signs of life around the villas).

We had no TV or radio in the apartment (what was the point when we couldn’t understand anything anyway?). Months later we bought a small stereo, but the only thing we occasionally listened to was the Voice of America broadcasts and the few cassette tapes of Serbian music we brought with us. My parents would regularly bring home a copy of Newsweek magazine, but it took me a while to be able to understand anything as it was only a few weeks after we arrived to Libya that I had my first English lesson. I started going to school immediately (school went from Sunday to Thursday, we were off on Fridays and Saturdays). There was a school bus that would take the kids from Hawari to the city center where the Serbian school was located.

The first day I went to school, I walked to some sort of Principal’s office, and gave the Principal my basic information. He said the school didn’t offer German (which was what I studied before I came to Libya and which, as a foreign language, was one of the requirements for graduation) and asked what my parents were going to do about that. I said I hated German anyway, and I was going to do three years of English in one. He nodded his head doubtfully and that was the end of our discussion.

The school was a joke. The building was small and dilapidated, the classes had between two and five students on average, and most of the teachers were unskilled and uninterested in what they were teaching. I had a great math teacher in the first few months, but then she went back to Serbia. That was the pattern that often repeated. When people’s contracts expired, they would go back to Serbia, and an untimely replacement would eventually arrive.

Fortunately, by that point in my life, I had good study habits and a good foundation in subjects such as math, physics, and chemistry. So I just followed the textbooks, and my parents helped, my mother with language and literature, my father with grammar, math, physics, chemistry, biology. History and geography I studied myself from the same ridiculous textbooks that followed me until I left Serbia. And I diligently practiced writing the letters of the Arabic alphabet. Every letter was written in a different way based on its position within a word (beginning, middle, end), and there was a forth version of the letter if it was standing alone. I filled pages with the letters the way I did in the first grade when learning the Serbian alphabet, but the Arabic language itself was beyond my ability to comprehend. The instruction our teacher (interpreter by profession) offered was pretty bad, with no real curriculum and no teaching experience on his part. I didn’t learn anything but how to write letters, and I didn’t care.

I made friends with kids that were around my age, and we hung out in the middle of the village, maybe sat on a bench and talked, or walked around the village. Occasionally we went to some sort of a “club,” which was the only thing there was in the village in addition to a small grocery store and the hospital. In the club, grown-ups (including my father) played chess, and we could occasionally watch a movie (with no Serbian subtitle) and drink tea with peanuts. (I have never learned anything about the origin of this drink that consisted of tea and peanuts that were in the actual drink).

There was not much to do. I was a budding teenager and I continuously longed for things. I wanted my country back, I wanted more friends, I wanted a “normal life” (“normal life,” I suppose, meant doing the same things teens did back home, which I am not sure was much different from what I was doing). I complained a bit, I was unhappy a bit, but I worked hard on my English and I was happy about my fast progress.

My parents worked a lot (according to Serbian standards), and I was learning how to entertain myself in the absence of TV, radio, movie theaters, restaurants. Occasionally my parents took me to downtown Benghazi, but it was mostly to do some kind of shopping. Silly shopping. To buy things you didn’t need. We could never buy anything we actually needed (for example, shoes, clothes, technology) as only traditional Muslim attire was available in the stores and maybe, maybe some technology at ridiculously expensive prices. If you happened to go to the few semi-empty department stores in Benghazi, and by any chance you decided to actually buy something, it would take forever (literally) for you to attract the attention of a store employee and pay for your purchase. Now Serbs were definitely not known for their great customer service skills, but the behavior of department store employees in Libya was beyond imaginable. They would simply stand in twos and threes and talk animatedly, gesticulate, giggle, and there was no way to attract their attention. First you maybe tried to make an eye contact, then you said “Excuse me” or the equivalent to “Excuse me” in Arabic, but they would absolutely not respond. They would continue to talk, simply ignoring you, and then, maybe fifteen minutes later, if you were still there, they would saunter lazily up to you and take your money. Numerous times my parents and I just put the stuff back onto the shelf and left the store. It really came down to how bad you needed something.

My parents worked a lot (according to Serbian standards), and I was learning how to entertain myself in the absence of TV, radio, movie theaters, restaurants. Occasionally my parents took me to downtown Benghazi, but it was mostly to do some kind of shopping. Silly shopping. To buy things you didn’t need. We could never buy anything we actually needed (for example, shoes, clothes, technology) as only traditional Muslim attire was available in the stores and maybe, maybe some technology at ridiculously expensive prices. If you happened to go to the few semi-empty department stores in Benghazi, and by any chance you decided to actually buy something, it would take forever (literally) for you to attract the attention of a store employee and pay for your purchase. Now Serbs were definitely not known for their great customer service skills, but the behavior of department store employees in Libya was beyond imaginable. They would simply stand in twos and threes and talk animatedly, gesticulate, giggle, and there was no way to attract their attention. First you maybe tried to make an eye contact, then you said “Excuse me” or the equivalent to “Excuse me” in Arabic, but they would absolutely not respond. They would continue to talk, simply ignoring you, and then, maybe fifteen minutes later, if you were still there, they would saunter lazily up to you and take your money. Numerous times my parents and I just put the stuff back onto the shelf and left the store. It really came down to how bad you needed something.

Most of the food we needed we bought at the small supermarket in Hawari, but there was nothing too fancy in the Libya of that time. When meat, eggs, or bananas would arrive, you had to wait in line for a long time and then buy large quantities of these foods. You never knew when the next delivery date was going to be. Libya was under sanctions then, and there was definitely a shortage of many foods.

There were sections of the city that were right on the water, with well-maintained gardens and palm trees, and maybe a tall building or two, but we never went there. Nobody went there. Libya had no tourists or foreign businessmen.

There was a modest Serbian library in the Serbian club that was located on the first floor of the building where my school was, and my father took me there often. I read whatever books the library had, books that were appropriate for my age and those that were not, like Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Spending many hours on our kitchen balcony, I started experimenting with water colors and temperas, ending up with some version of sunset and a lot of playful “abstracts.” I made carrot cookies that were actually edible, and started making paper and cardboard decorations for my room. My room became the cleanest room in the house. I started keeping a journal, and I wrote often. I spent time with the few friends of similar age I had, and I went to whatever birthday parties I was invited to. At one of these parties, a brother of my Albanian classmate, one of the few people that were older than me, asked me to dance with him and that was it – I was in love. My journal started filling fast. I celebrated every instance of seeing this boy. Directly, or from the window of my room. A few years later, I laughed at the number of specially decorated journal entries that looked like this: I saw Bini. He said hi. It didn’t look like I wanted from him much more than that.

I guess I was lonely. And I was definitively very nostalgic. Maybe it was the first time I felt that emotion. I longed for the people I cared for, but even more for the places I left behind. That surprised me, the fact that I wanted back the city I never particularly liked. That from afar, I loved and terribly missed everything and everybody. I wrote a few letters, I received a few letters, but I was definitively never much of the letter-writing type. I daydreamed. I walked around the village. By the time mimosas bloomed, I accepted Libya for what it was. A slightly strange, lonely place for a foreign teen to be. And a paradise on earth in some ways.

When You Get to Reading and Writing…

My son is only two, but I think about teaching him how to read and write in Serbian. I know we are a few years away from that point, but I am savoring the thought. Serbian is a phonetic language, it has two alphabets, Cyrillic and Latin, and it has thirty letters and thirty phonemes, that’s it. It’s all pretty simple, thanks to Vuk Karadzic who revised the Church Slavonic (staroslovenski) language and came up with this pretty simple version of Cyrillic alphabet, with a simple premise: Pisi kako govoris, citak kako je napisano (Write as you speak and read as it is written).

My son is only two, but I think about teaching him how to read and write in Serbian. I know we are a few years away from that point, but I am savoring the thought. Serbian is a phonetic language, it has two alphabets, Cyrillic and Latin, and it has thirty letters and thirty phonemes, that’s it. It’s all pretty simple, thanks to Vuk Karadzic who revised the Church Slavonic (staroslovenski) language and came up with this pretty simple version of Cyrillic alphabet, with a simple premise: Pisi kako govoris, citak kako je napisano (Write as you speak and read as it is written).

Maybe, just maybe, the very thought of Serbian being so easy to read and write once you can speak it gave me the courage to embark on this bilingual journey with my son. How can I allow my son, I was thinking, to live his life without ever reading the authors who wrote in Serbian/Croatian/Bosnian, only few of whom have been translated into English? Milorad Pavic, Ivo Andric, Milos Crnjanski, Bora Stankovic, Jovan Ducic, Serbian folk songs, fairy tales, Ne daj se, Ines…the list can go on and on….

In case you are getting ready to start teaching your child how to read and write in more than one language, here is a great article that offers plenty of practical tips, Teaching Children to Read and Write in More Than One Orthography: Tips for Parents, published in the Multilingual Living magazine.

Raising a “Happily Bilingual Child”

No matter how much I instinctively trust my son’s ability to somehow sort out the two languages he is learning, there is always a slight fear on my part, or maybe just a thought, that at some point, in some way, two languages might confuse him. It’s not something I think about much as I have committed myself to teaching my son Serbian in addition to English, period. But, I love to see studies like the one cited in The New York Times’ article Hearing Bilingual: How Babies Sort Out Language. The article explains “not just how the early brain listens to language, but how listening shapes the early brain” and goes on to conclude that “bilingual children develop crucial skills in addition to their double vocabularies, learning different ways to solve logic problems or to handle multitasking, skills that are often considered part of the brain’s so-called executive function.”

This is yet another study to show the benefits to bilingualism, which comforts me and encourages me to try harder to give my son Serbian. And the article mentions somewhere the “happily bilingual child” and acknowledges the fact that “there aren’t many research-based guidelines about the very early years and the best strategies for producing a happily bilingual child.” Yes, I’d like to be see more research done in this area, and consequently some guidelines on how to raise “a happily bilingual child.”

Oftentimes I think about the possible emotional consequences of bilingualism. I consider myself to be bilingual, but the kind of bilingual that differs from the kind my son is going to be. I was thirteen when I was introduced to English, and I had Serbian “in place” when I started learning English. And I have to admit that I have always felt like the two languages were slightly at war within me. In my life in the US, many times I felt like I had to suppress my Serbian, or at least some aspects of my Serbian, in order for the same aspects of my English to flourish. I am not happy about this, but I am happy as long as I have at least one language fully available when I need it. For example, I write my stories and this blog in English, and I feel English will be my dominant language in the area of writing as long as I live in an English-speaking country.

I wouldn’t call myself an unhappy bilingual, definitely not, but I hope my son has an easier time being bilingual. I kind of count on it as he is absorbing both languages at the same time. But I’d definitely like to see more studies covering the area of “happy bilingualism” and hear other people’s stories of bilingualism.

Forget the Grammar Please

My son likes to play with the little girl next door. She is four months older and as persistent as he is. As intense as he is. Maybe that’s why they get along. Or don’t. Andrei tried to hit her a few times and managed to hit her once or twice. Caroline tried to punch him once and she seems to be physically stronger and more capable of wrestling toys out of Andrei’s hands.

My son likes to play with the little girl next door. She is four months older and as persistent as he is. As intense as he is. Maybe that’s why they get along. Or don’t. Andrei tried to hit her a few times and managed to hit her once or twice. Caroline tried to punch him once and she seems to be physically stronger and more capable of wrestling toys out of Andrei’s hands.

This being said (nothing really atypical of two-year-olds), Caroline and Andrei love each other. They genuinely enjoy each other’s company. Sometimes they play literally together: Andrei plays the drum and Caroline plays the guitar as they are performing for me; they hide in the tent in Andrei’s room and ask me to look for them. More often they do the “parallel play” typical of two-year-olds: she makes snakes from play dough, he is trying to bounce the ball. When we don’t have a play date for a few days, I am sure to hear all sorts of things, Wonna see Taya; Taya’s house; Taya’s phone; Taya hot (After I ask Andrei if he is hot and after he says, Yes.). Taya poopies. Taya this, Taya that. When they finally see each other, Caroline and Andrei run towards each other in a way that reminds me of Gone with the Wind.

We see Caroline quite often. She stays at home with her dad. Her dad and I exchange babysitting services often (hence the time to actually start this blog). It’s quite a great arrangement. But Caroline, of course, doesn’t speak Serbian. And I am trying to make the time Andrei and I spend with Caroline NOT be English-only time (in a way that’s not imposing, unfair and disconnecting).

At first, Andrei and my time with Caroline was exclusively in English. After an hour or so of my speaking to Andrei exclusively in English (Andrei might manage to squeeze in vodida, which is Andrei’s version of the Serbian word for water and Andrei’s dominant word for water), something just wouldn’t feel right. Of course, it was definitely easy, very easy, for me to speak to Andrei (or anybody) in English, words would come easily to me, precise and light, on the surface it was all good. Maybe it was guilt that got me tangled up in that sense of things not feeling quite right. Maybe my determination to teach Andrei Serbian and therefore my commitment to not be without Serbian during the day, which was my primary Serbian time with Andrei.

So first I started with the Serbian version of Ring Around the Rosie, Ringe Ringe Raja. Andrei had always liked this (unlike Ring Around the Rosie, which he tended to refuse to participate in when our playgroup leader would sing it). Caroline started liking Ringe Ringe Raja too so every time we got together, Andrei, Caroline and I would do our Ringe Raja circle dance many, many times. Caroline even became the most frequent instigator. I would sing, Andrei and Caroline would even go as far as to repeat the last word of each line, and then we would all squat down at the end and pretend we were falling down, and we would continue to roll on the floor and laugh.

Next I started taking each opportunity to count in Serbian. When we would go up the stairs or down the stairs, we would all count. Jedan, dva, tri, cetiri, … deset. I would be the leader, Andrei and Caroline would do quite a good job of repeating the numbers in chorus. Caroline’s pronunciation would often be quite clear.

Then I tried to infuse even more Serbian in Andrei and my time with Caroline.

Puppy, Caroline and Andrei would say at about the same time.

Puppy is barking, I said. Kuca laje, I repeated in Serbian.

Now this approach seemed to have some side effects.

A minute later, Caroline pointed to my Franklin Institute “bracelet” that was still on my wrist from the trip Andrei and I took earlier in the day and asked, What’s that?

Narukvica, I answered in Serbian.

Buba Duba Buba (or something that sounds like that), Caroline said. I realized that I switched to Serbian without even noticing. I corrected myself, That’s bracelet. I was shocked that I got confused so fast, so easily. My brain is only capable to handle one thing at a time. Period.

Andrei and Caroline continued to ride their bikes. I followed them and continued to provide comments in two languages. Ray is fixing his car. Rej popravlja kola. Yes, that’s a tree. With pointed leaves. Drvo, sa ostrim listovima. And then, I yelled, Stani! Stani! Stani! Okreni se, as Caroline and Andrei were heading towards the busy street. Andrei stopped, Caroline didn’t so I ran after her, saying Stani, and then it hit me, Stop! Stop! That was the right word.

There are some major differences between Serbian and English, and I am afraid those are working against me. Maybe I shouldn’t even think about them, but sometimes I do, probably because I am aware of the fact that I am the totality of Andrei’s Serbian (plus some books and some music). I am aware of the fact that there is no real, organic need for Andrei to speak Serbian (after all, I speak English). Of course, I am trying to create some sort of emotional need, but…am I doing a good job? Will Andrei trust my love for Serbian when I write my stories (and this blog) in English? Will he be able to sense and absorb the love that I have ingrained in me and can never part with it because I was born there and grew up there and had Serbian as my only language for quite a few years.

Yet, I can’t help noticing some things that are working against me. Serbian words are long with a lot of “ch” and “sh” sounds. Compare shoe to cipela, fork to viljuska, bowl to cinija, trip to putovanje. Sometimes it feels funny when I say this long Serbian word, and in the second I am saying it, I hear the English equivalent in my head, a single syllable, so easy, one beat. The English word seems to be just so much easier to remember. So…my job here is to somehow motivate my son and teach him to appreciate the melodic qualities of the Serbian word. To disregard the length. And the number of syllables. To like the winding ways of Slavic languages.

What about the Serbian grammar? In English, my son is quite familiar with “that” and “those.” That house. Those shoes. He’s been practicing these two pronouns for many months. In Serbian, I try to say, Ta kuca, simply to indicate the gender and maybe the category of number (singular), and I am trying to forget about the cases (that’s why I wanted Andrei to learn Serbian at the same time he was learning English; otherwise he would actually have to memorize and make sense of twenty-one forms for one English “that” and that just sounds cruel unless it’s your native language). But whenever I say a sentence in Serbian, and most sentences include at least two nouns, at least one of which is most likely in a case other than nominative, part of me feels powerless, My love, I don’t know how to help you with this! You just gotta figure it out! For example, Hoces da zoves babu? (Do you want to call grandma?). He repeats babu, I say baba, because unless it’s used in a sentence, the word babu doesn’t make much sense, the actual word is baba. And I can’t help comparing this to English, where you have one simple form, Grandma, no matter what you say. Grandma is going shopping. You want to show your book to Grandma. You want to see Grandma. It’s always Grandma.

Then I try to stop myself. I can’t control much more than the quantity of Serbian I give to my son. So I better just keep talking. In Serbian. Without thinking too much.

One Language or Two?

So if I had had a child ten years ago, soon after I came to the US, raising my child with bilingualism and biculturalism in mind wouldn’t have even become an issue. I went through a strange process when I first came to the US. I simply wanted to belong. I wanted to belong to no matter what. I wanted to be same as people around me, and I mostly went for the Americans who looked most American to me, those who wore shorts and sneakers like the tourists I saw in Belgrade, ate pizza for dinner and spoke accent-less English (here I mean the absence of a foreign accent as I was definitely not able to distinguish between different American accents such as, for example, Southern versus New York).

Maybe it was all about English. Maybe I felt that if I changed myself on the outside (put away my flowing flower-patterned dresses and skirts and switched to shorts and sneakers), English was going to flood my mind and lodge there, grammatically perfect, beautifully fluent, and accent-less, and Serbian, which many times felt like an obstacle to speaking perfect English, was going to be pushed into the far background. Little did I know that seven or eight years later I was indeed going to reach a point that looked somewhat like that (minus the accent and occasional grammatical uncertainties that were still present) and that I was going to feel like I was missing a limb, or even maybe an entire half of my body.

I sometimes wonder if other foreigners go through this process. And if the process I went through was indeed driven by my idea of complete immersion in the English language. The more I think about it, the more certain I am that English was the main force. After all, I only came to this country because it was one of the few countries where people spoke English and that was, at the same time, going to let a Serb in for an extended period of time (a year in my case, as an au-pair). Before I came to the US, I was a student of English language and literature at the University of Belgrade and I left the country before I graduated. After seven years of studying English language and literature at the university level, and six more before that, I was not fluent in English – after all, in most of those years I had very few opportunities to speak English. The language classes at the University of Belgrade consisted of lectures, translation and grammar exercises and some useless essay-writing classes, and the literature classes included endless lectures about books and texts where you were told what they meant and at the end of the year you were supposed to spit the same information back at your professors, mostly in Serbian. You took an exam at the end of the year, and then you were able to keep retaking it depending on how many times you flunked, and nobody ever – ever – questioned the ability of your professors to teach, even if ninety percent of their students failed. While taking an oral exam, you had one or two or three professors sitting in front of you and a room full of your fellow students (thirty or forty on average) sitting behind you, waiting to take their exam, and in this lovely, stress-free setting you were supposed to let your English shine.

Well, my English didn’t shine. I was terrified, numb with fear, and I made grammatical mistakes that I knew were mistakes the second the sentences came out of my mouth. It felt like my mouth and my brain were never in sync, my brain frozen more often than my cheap Dell computer, and my voice unreliable, stuck in my throat.

I felt terrible about the whole thing: I, a-straight-A-student in my entire school career before the University of Belgrade, who managed to be one of the fifty-five students accepted in 1991 by the University of Belgrade to study English, felt like a complete failure. And at that point I didn’t even care if I were ever going to graduate, but I desperately wanted English, that English that I fell in love with years before, when I was in seventh grade, to flow easily from my brain to my lips, like a language should. And I wanted to be able to relish in the process.

In the only other country in which I lived for an extended period of time, Libya, I never went through the same process of abandoning my Serbianhood. The whole experience was very different. I was much younger, only thirteen when my parents and I came to live in Benghazi in 1985 and fifteen when we left. It was in Libya that I received my first English lessons. Unlike with German that I started studying a few years before that, and Arabic that I studied at the same time I studied English, I loved the magical flow of English in my brain and my mouth, and I even tried to keep my diary in English as soon as my vocabulary reached about 100 or 200 words.

The Libyan world was vastly different from the world I grew up in, and I never even tried to compare the two. My parents worked for the 7th April hospital in Benghazi, and we lived in a village located right next to the hospital, completely separated from the Libyan world. I went to Yugoslavian school and played mostly with Yugoslavian kids (Yugoslavia was my country until it fell apart in 1991). I had some curiosity about the male and female segregation typical of Muslim cultures, but that was about it. Largely, I didn’t care about much more than the mimosas blooming under my window, beautiful sunsets over the flat red land, wild sandy beaches and the pleasant Mediterranean climate (perfect for me as I have always loved the heat). In 1987 I went home, and I felt somewhat changed by the experience, but merely by the total absence of TV, radio, and any other form of mass communication, which forced me to read books, write, draw, paint, do crafts. Overall, I went in Libya through nothing that even remotely resembled the process I was going through in the first few years spent in the US.

My life in the first few years in the US kept changing fast. First, I was an au-pair, and I had quite a few hours during the day to myself (I took the kids to daycare/school in the morning, and then I was free until at least three in the afternoon). I had weekends to myself too, and I went from being somewhat of a tourist exploring the Smithsonian museums, Lincoln Memorial, Jefferson Memorial to strolling by the Potomac and making my way to the Serbian Church in D.C.

In the Serbian church in Washington, D.C. I felt far from welcome at first. Distanced enough from my own culture, I clearly saw what Serbs were like: once they got to know you, you were their best friend, they would die or kill for you. But before they got to know you, well, you were just a stranger. They would never just drop a casual hello or talk to you about the weather. So, the first few times I went to church, I hardly spoke to anybody. But I kept going, despite the fact that I wasn’t the churchgoing type (I made friends with my spirituality in my teens and started going to church occasionally, but usually at random times, when I felt like it, when the liturgy was not in progress and when I could have just a few minutes of silence to myself, to ponder, pray, remember, whatever). But now, I was lonely enough that I kept going to liturgies religiously, hoping I would eventually make some friends.

I felt far from welcome at first. Distanced enough from my own culture, I clearly saw what Serbs were like: once they got to know you, you were their best friend, they would die or kill for you. But before they got to know you, well, you were just a stranger. They would never just drop a casual hello or talk to you about the weather. So, the first few times I went to church, I hardly spoke to anybody. But I kept going, despite the fact that I wasn’t the churchgoing type (I made friends with my spirituality in my teens and started going to church occasionally, but usually at random times, when I felt like it, when the liturgy was not in progress and when I could have just a few minutes of silence to myself, to ponder, pray, remember, whatever). But now, I was lonely enough that I kept going to liturgies religiously, hoping I would eventually make some friends.

Gradually, I made my way to the room where people hung out after the liturgy, and I made friends. I became one of them, and when NATO bombed Serbia in 1999, before my au-pair year was over, when the U.S. offered no solutions – absolutely no solutions – for Serbs who happened to be abroad when the bombing started and whose visa expired and who needed to go home while NATO was still striking Serbia every night, I wouldn’t have made it without the people from that church.

In September that year I was in school in Philadelphia studying nothing else but English literature (I was able to transfer two years’ worth of credits from the University of Belgrade, but based on how little I learned in Belgrade, I later thought my Philadelphia school shouldn’t have accepted anything). An au-pair year behind me, I was sharing a dorm room with eighteen-year-olds (one of the conditions of my scholarship was that I had to live on campus), feeling much older than I really was (not so bad age of twenty-seven). I read literature and I wrote about it. English was flowing through me, and I was happy. First of all, I was happy because I was writing, and then, it happened that I was writing in English. I delighted in the process. Maybe, since the day one when I started studying English, or since the moment I decided I loved that language (the way I never liked German), my idea of foreign language mastery was to be able to write in it, to bask in it, to play with it the way I was able to in Serbian.

Now one might ask why I just didn’t stay with my native Serbian and make things easy for myself. Why I needed English to begin with. The honest answer is, I don’t know. Maybe because since the moment English entered my life, years ago, when I was living in Libya, it was always a major part of my education. First, as I started studying it in seventh grade, I had to do four years’ worth of material in only two years to be able to graduate from the school I attended in Libya. Then, In high school, I chose a course of study that included a lot of English split into three different subjects. Finally, at the University of Belgrade, I studied phonetics, morphology, syntax, and tons of most detailed grammar. After all these years, I desperately wanted to reach that point where my English was as good as my Serbian was. To be able to write as well as a native speaker would. To write my stories in English. I couldn’t write my stories in Serbian when I was now living my life in English.

By the time I got out of school, I fully owned my English. I used Serbian only when talking to my mother, which wasn’t often. I got a job as an editorial assistant for two trade magazines and was quickly promoted to an assistant editor. I started writing my own fiction. In English. And I started forgetting my Serbian. For real. When I talked to my mother, despite all of my focus and effort, more English than Serbian words would come out of my mouth. I strung words together following the syntactic rules of English. You forgot your native language, my mother said once emphasizing every single word. The whole thing was funny and not funny. I was amazed at the process (Can you really forget your native language? Really?) and then I couldn’t escape the feeling of actually losing something. A Serbian saying would come to my mind (the one that doesn’t have an equivalent in English): Igracka-placka. Something you would say to a kid who is playing happily when he or she gets hurt in the process. You play and then you get hurt. Oh, well! You are OK! And indeed I was OK for a few years. I loved my English. The whole thing reminded me of my high school days when I fell in love with a pretty obese boyfriend, and I started gaining weight, for unclear reasons (for fun, or to look more like him and keep that wandering-eye-boy interested in me). I was gaining 2-3 pounds a week, I out of all people, the always too thin I. I thought the whole thing was funny. Until I realized my face got buried in the weight of my cheeks and I really needed to lose those twenty pounds I gained, which was not that easy.

Over the years, I built a life for myself in the US. I had the job I loved, I wrote stories, I made friends. I fought with my mother over the phone. I fought battles that I felt I should have fought years before then, but it was only then that I was strong enough to confront my mother. I sought answers in therapy. I dated men. I decided I wanted to have a family. I met my husband. We had a baby.

I held my son in my arms. I spoke to him in English and I called him sweet names. First he was Babika, then The Little Man, then Adoricus and Cutolino, and many other things. I tried singing to him in English, but I didn’t know the lyrics of many of the nursery rhymes. So I just hummed, and then I started making up both the lyrics and the tunes,

My baby, my baby, my baby maybe,

My baby, my baby, my maybe baby.

And around that time, my Serbian started coming back to me.

Tasi, tasi, tanana,

Evo jedna grana,

the way my mother and my aunt sang to me. I ordered a book of Serbian poems, Riznica Pesama za Decu by Jovan Jovanovic-Zmaj, the same one I had when I was a kid, with a yellow cover that had a bunch of kids flying a kite (the poet’s nickname is Zmaj, which means kite in Serbian). The book brought to life all those days I spent with that book, sometimes reading it, but before even I knew how to read, copying the illustrations from the book.

As I was reading the poems to my son in the first few months of his life, my voice bounced off the walls and I fell in love with the sound of my native language all over again. Actually, I never stopped loving my language. It was just that I felt my English and my Serbian were mutually exclusive. That they couldn’t comfortably co-exist in the pretty ADD me who couldn’t handle more than one thing at a time. Switching between two languages made me crazy. Like I couldn’t fit both of them into me at the same time. I needed one language in which I could write, and that was English.

A few months went by. My husband approached the subject again. I’d really like you to teach Andrei Serbian, he said.

Do you know how hard that would be? I responded, convinced he didn’t and couldn’t really know how difficult it was for my brain to handle two of anything.

Still, I often sang to Andrei in Serbian, and kept repeating, mama, tata, baba, deda. Every now and then, I would play a you-tube video of some Serbian song: Tata kupi mi auto, Tata, pa ti me volis.

My son started sitting, crawling, walking (way too early). At eight months he got his first word out – mama. I have always felt that in English that word is more a means to an end than an end in itself. Mama coming out of a baby’s mouth soon becomes Mom or Mommy. In Serbian, mama is the ultimate. Mama.

Maybe that’s when I decided. Maybe a little later, when our Irish friend yelled at me (or just spoke to me in his typical voice with a strong Irish accent), You’re really not going to teach Andrei Serbian! ?!

The decision was somehow made. It evolved. I needed to try. I needed to do the best I could, like with everything else.

I ordered a book on raising bilingual children, Raising a Bilingual Child, by Barbara Zurer Pearson. A pretty good book, very informative. I found out about how other parents did it. I examined the logical strategies outlined in the book: One Parent-One Language; Minority Language at Home; Time and Place; and Mixed Language Policy. I acknowledged the fact that I was going to be it, no support system, only me, some music and some picture books. I knew I was not going to use any one of the techniques exclusively simply because I was not organized enough and the effort to do it would have killed me. But I decided I was going to try to speak to Andrei in Serbian anytime we were alone, and later I added an addendum, I was going to try to speak to Andrei in Serbian even when other people were with us, except when the other person was my husband and then, of course, we wanted to have family time and to understand one another.

So I started trying to speak to Andrei in Serbian whenever we were alone. In the beginning, I mixed English and Serbian a lot. A Serbian sentence with at least one English word. Or, a Serbian sentence, followed by an English sentence, and then a Serbian sentence. Or, three Serbian sentences, followed by three English sentences, the last one of which included a Serbian word.

It got better over time. And easier.

On some days I feel I get a lot of Serbian into our day. On some other days, I am not pleased with myself. I feel I give in to English too easily. I feel I should try harder.

Overall, I feel good about Andrei’s progress. He turned two a month ago, and English is definitely his primary language. He understands Serbian, he can say quite a few words, and he is just starting to string Serbian words together. I remind myself that whatever I accomplish is better than if I never tried.

And I keep talking and singing to my son. In my native language.